By Castle Ho‘onanea Team | Photos Honolulu Star-Advertiser

On the easternmost margin of Waikīkī, rising from the edge of the sea and sweeping majestically into the clouds, is the furrowed hillside known the world over as Diamond Head. Movies and postcards have helped turn the crater into Hawaiʻi’s most recognizable landmark, and social media certainly hasn’t ebbed the attraction’s soaring popularity. The state monument welcomes upwards of 3,000 visitors a day, streaming to the summit, eager to capture a golden sunrise, crimson sunset or sweeping panorama of Waikiki’s skyline. Who among them gazes across the 175-acre floor of the crater, aware of the wildly divergent segments that mark its history, from battle-ready military zone to hippie mecca, and ultimately to a protected natural park?

The place is known as Leʻahi in Hawaiian, referring to its shape which resembles the brow of the ʻahi (tuna), while also potentially translating as “wreath of fire,” alluding to the practice in ancient times of lighting fires along the rim as navigational lights. Its English name was derived when 18th-century explorers discovered calcite crystals in the crater and mistook them for diamonds.

Diamond Head was once home to dryland forests and a wetland lake that swelled to cover half the crater’s floor during heavy rains, attracting a variety of waterbirds. By the early 1900s, the forests were gone, having succumbed both to grazing land for cattle and kindling for fires. The lake was also gone, due to construction that paved the way for a military-only presence from 1906 to 1968.

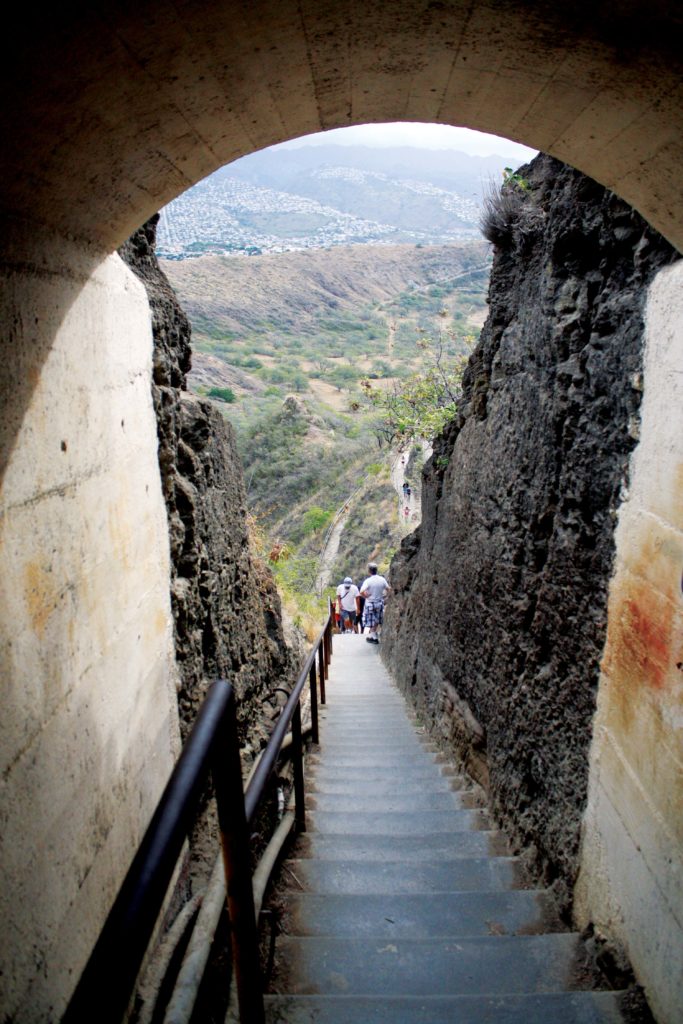

In 1908, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used mules and soldiers to build the trail that currently guides visitors in a zigzag up the mountainside, up to two steep flights of stairs, through a tunnel and up a spiral staircase that once housed a four-level Fire Control Station (that oversaw tactical battle operations). The trail surfaces at the top of the rim in a bunker housing live artillery. Today, countless visitors retrace those very steps in their climb to the top. Above one stretch of stairs, a series of freestanding overhead beams, whose purpose now seems perplexing, were once used to place camouflaging.

At least five tunnels, two for entry and three for battery stations, as well as additional hidden sites of military significance were also erected, including a cable device used to hoist equipment uphill. Its concrete vestiges can still be seen at a lookout point along the trail. The overall development was part of a coastal defense system that was advanced for its time. Stations on Mount Tantalus, Fort DeRussy, and Fort Ruger, which rested at the foothills of Diamond Head and controlled the crater’s firepower, had the capacity to calculate the position of a ship, without radar. Cannons and mortars were at the ready, but no artillery was ever fired from these locations during wartime.

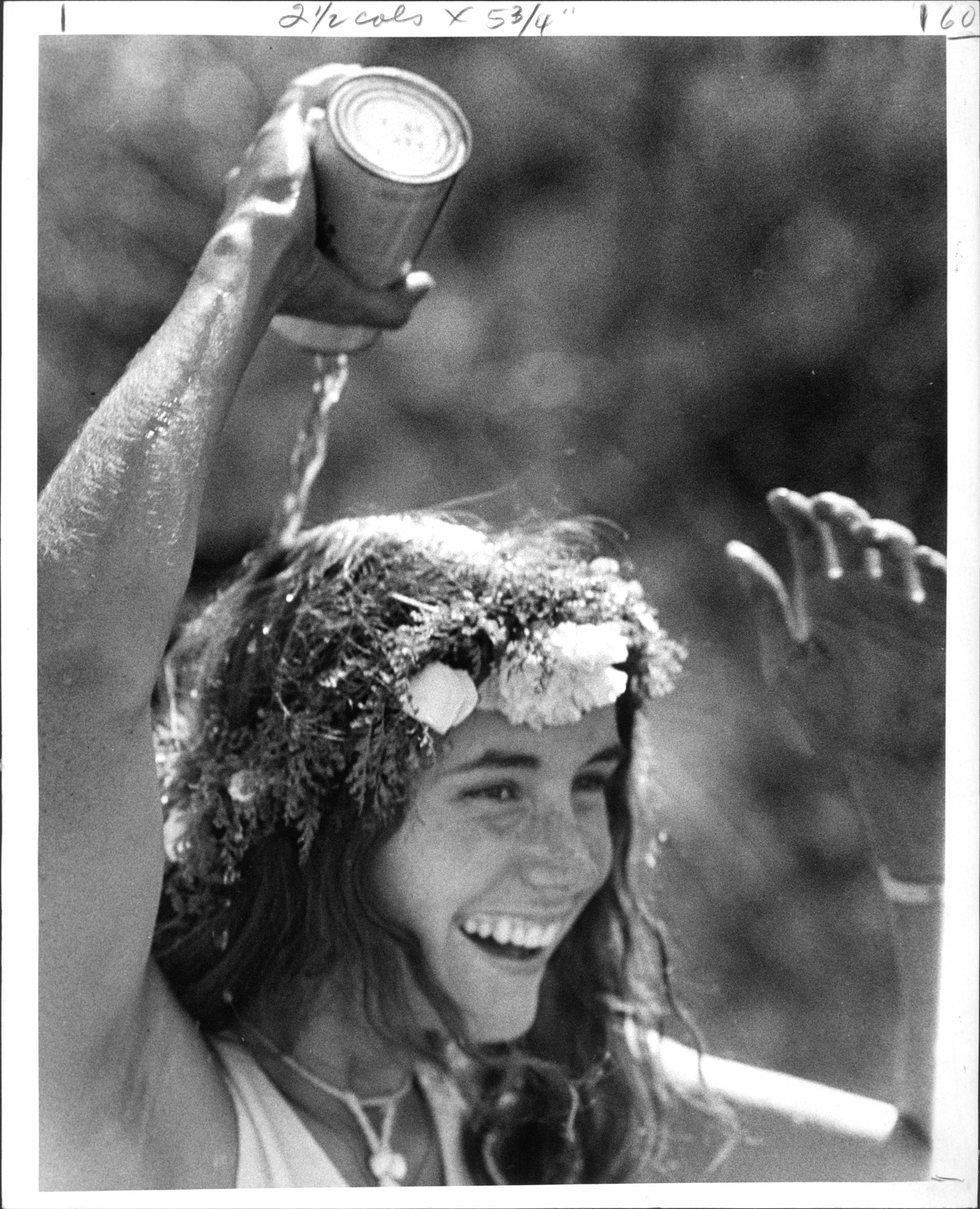

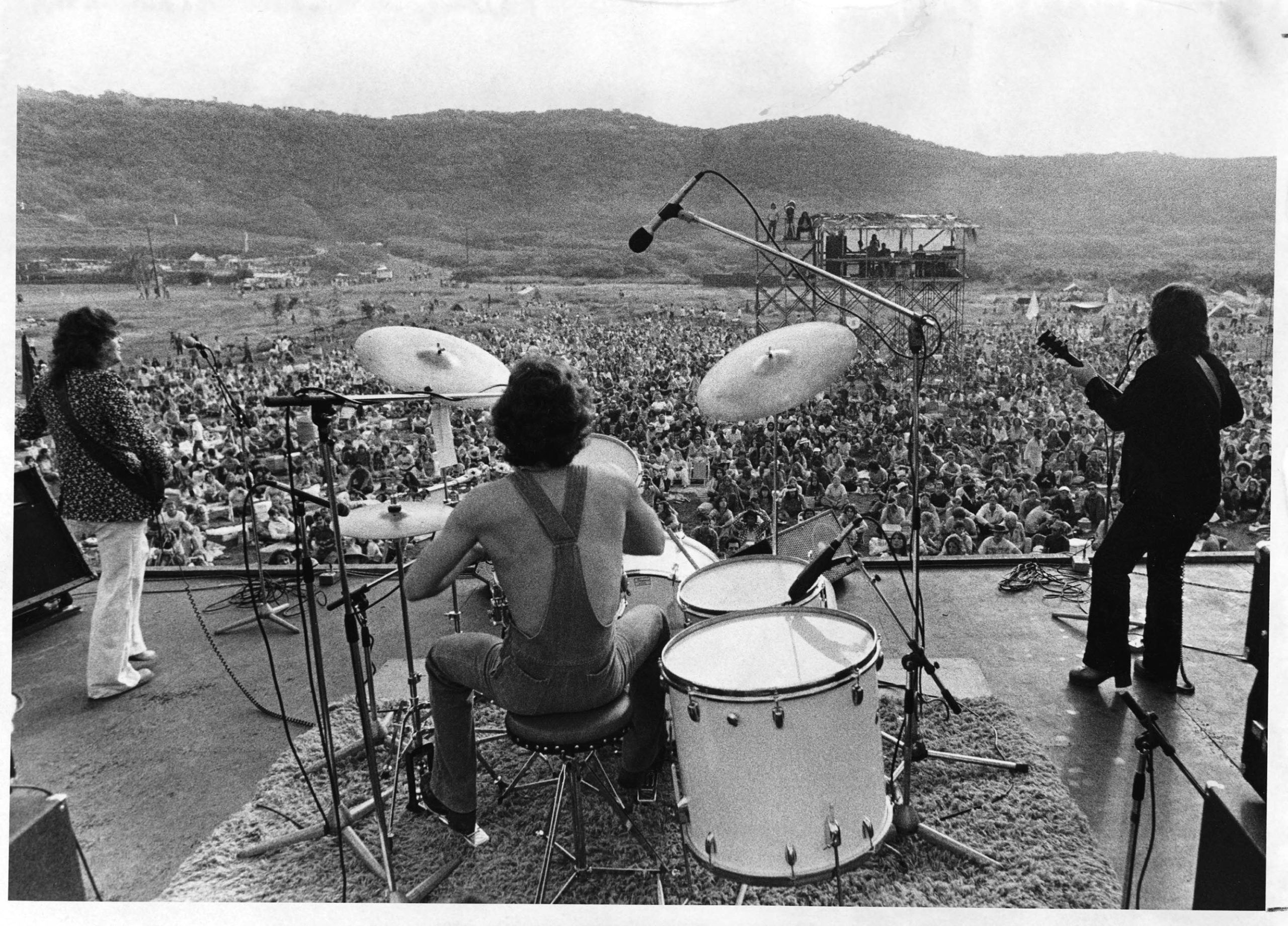

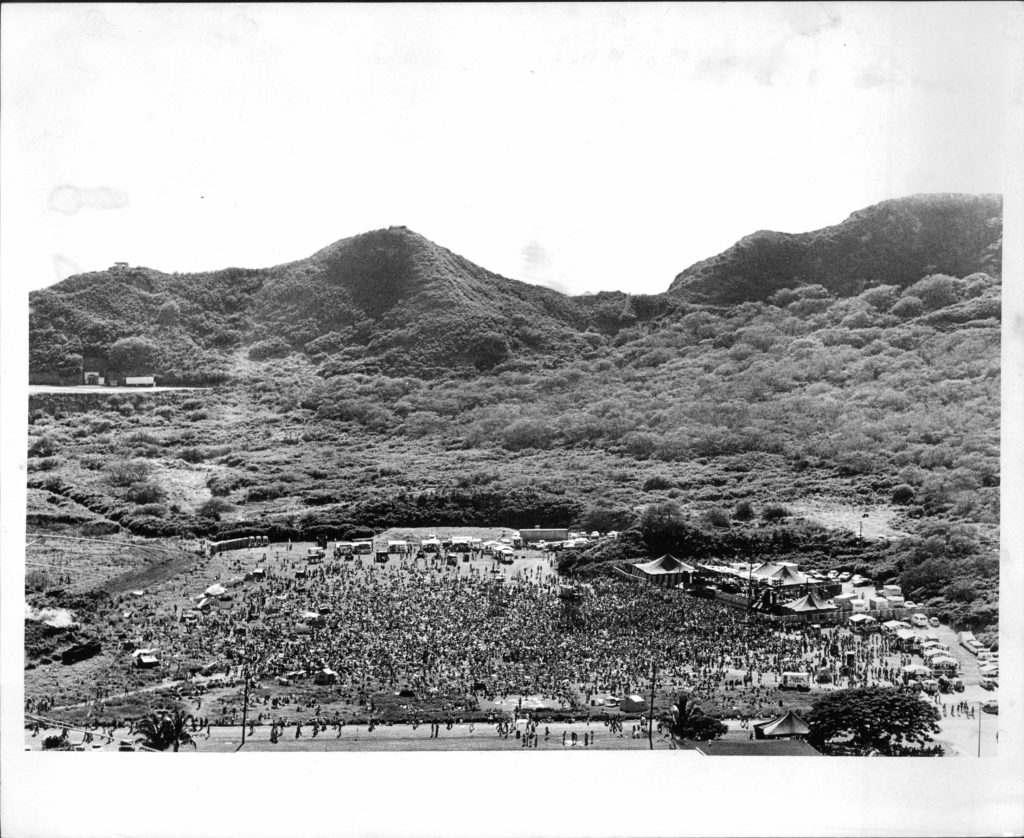

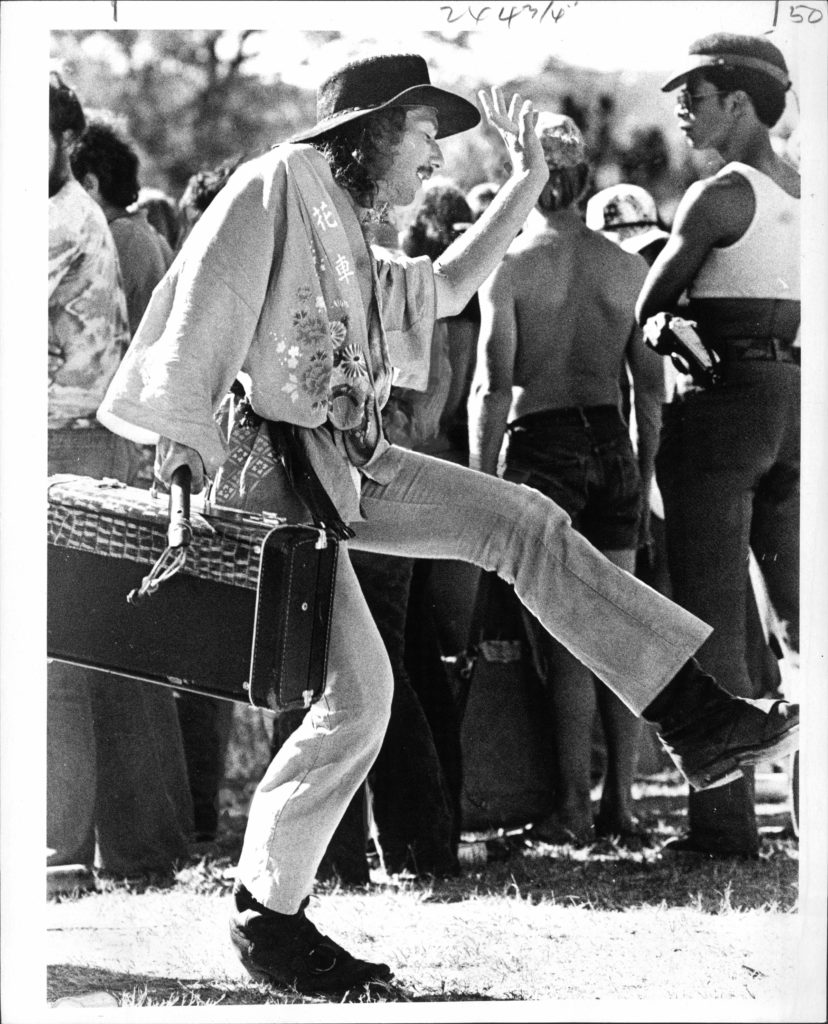

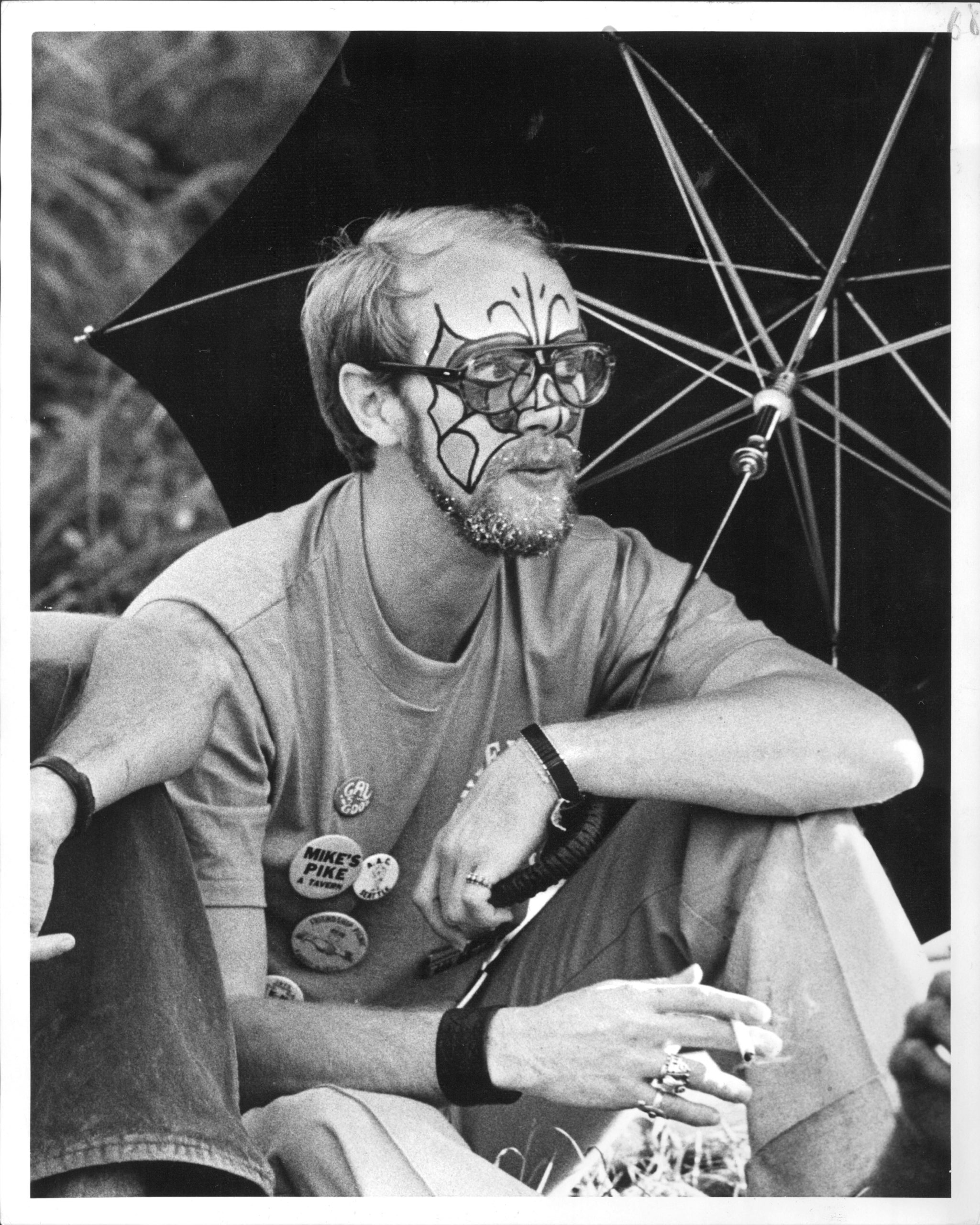

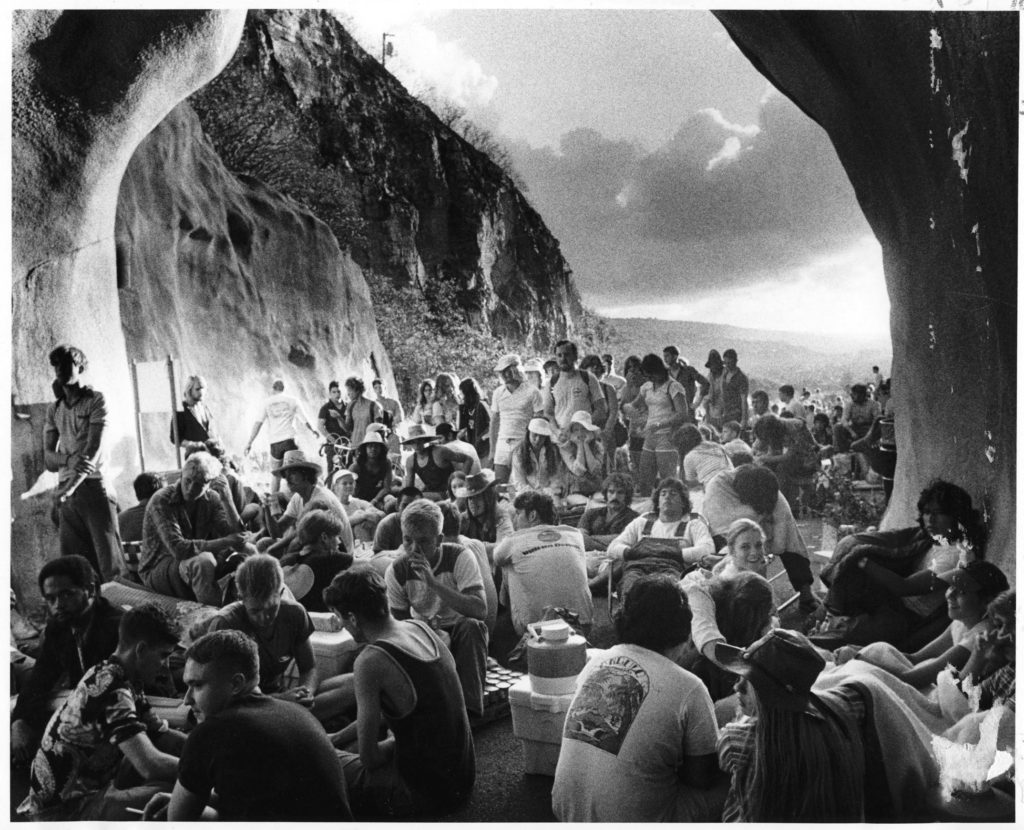

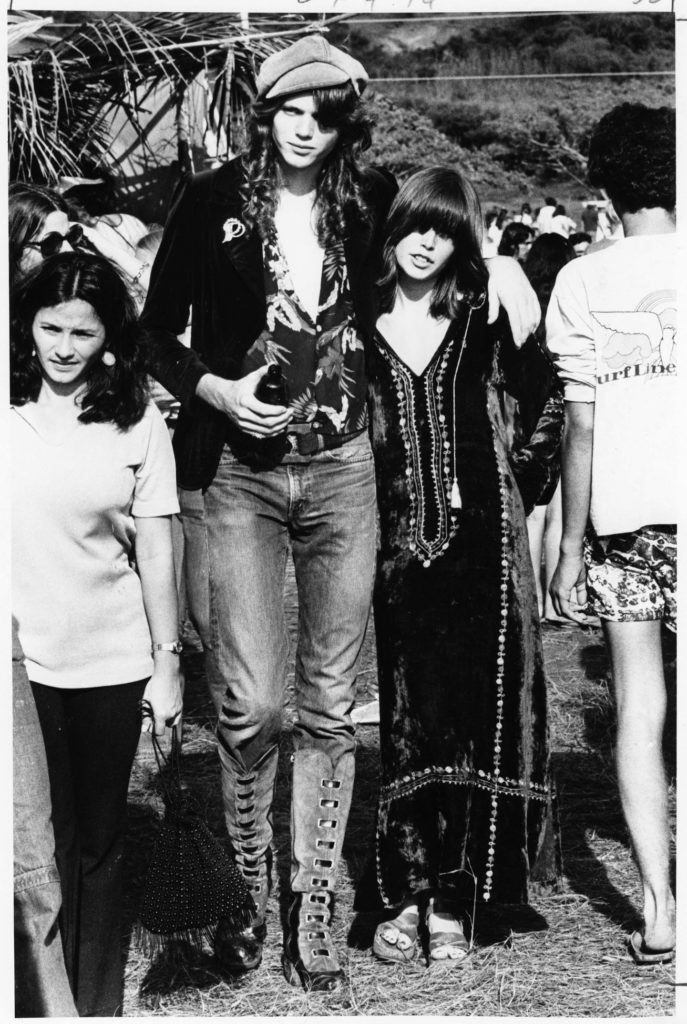

That most countercultural of years—1969—ushered in a wild incongruity at the park. Diamond Head dropped its fatigues, ushering free-spirited throngs to its annual Sunshine Music Festival, referred to more commonly as the Crater Fest. People poured in through the entrance tunnel and via unofficial trails over the rim. By the festival’s third year, the mass of 12,000 had swelled to a congested sea of 75,000. Their electric smiles lit up their faces as they danced, their hair long and free-flowing, with some of the revelers minimally clothed or even unclothed. Others were passed out on the ground. While yet others picnicked, savoring fresh coconuts and mangos.

Admission was free, and appearing live at the mic were none other than the likes of Santana, Journey, Jefferson Airplane, and Fleetwood Mac, along with local musicians Cecilio & Kapono and Makaha Sons, interwoven with the Hare Krishnas leading the crowd in chanting accompanied by drums and cymbals, as well as appearances by Cheech & Chong. As the years went by, the festivals stretched on to last two days straight, the participants mushroomed in a haze of smoke.

By the late ’70s, the happy-go-lucky era had run its course and the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) stepped in to phase out the fests in favor of the development of the crater interior. Numerous proposals had been put forward over the years as possible uses for the crater, from a zoo, golf course, sports park, or theme park, to a place for camping and hosting festivals. However, DLNR voted against commercial use in order to conserve the semi-wild nature of the park as much as possible. With that effort in mind, the park now includes a visitor area with a gift shop and large informational panels at the base of the trail. Visitors may also opt for a self-guided audio tour that illuminates the history, geography, and flora, and fauna of the area. Meanwhile, a new looped section has been erected at the peak, to ease the flow of foot traffic.

These improvements continue to happen in increments, with an overlying mission to preserve the crater as a natural, cultural, historical, and recreational resource. With these changes, however, there are no signs left of five heiau (or ancient temples) that once dotted the land. They were dedicated to the wind god, in hopes of keeping navigational fires atop the slopes alive. And though the dryland forests are gone, introduced flora and fauna have taken hold. The land’s natural features now include tall grasses and shrubbery, and at least nine species of birds that frequent the habitat.

Future plans call for new lookouts and trails to the rim, access to historical features, and improvements to pedestrian and vehicle flow.

All the while, cars continue to stream through the entrance tunnel from dawn till dusk, their passengers eager to experience this most famous of Hawai‘i’s landmarks. It’s a rare few who visit that have an inkling of the place’s complex and comprehensive history